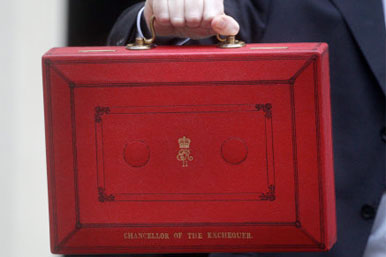

The Budget was headlined by economic downgrades and by the proposed imposition of a sugar levy on soft drinks, but for the commercial property industry, it was the amendments to the stamp duty legislation that will have most relevance.

The Chancellor altered the means by which commercial stamp duty is calculated, along the lines of the residential approach which he introduced last year. While the more progressive means of calculating the duty payable is to be welcomed, the sting in the tail was a 5% band introduced for purchases above £250,000. The other band of 2% applies to the amount of the purchase price between £150,000 and £250,000. No tax is payable on purchases below £150,000. Compared with the former approach, the new method increases the amount of duty paid on purchases above £1.05m. Given the cost of most commercial properties, all bar the very smallest are likely to face higher duty, which will impact on property’s performance.

The sugar levy, to tackle childhood obesity and due to commence in 2018, could raise as much as £520 p.a. with proceeds used towards increasing funding for sport in schools.

In a further move involving the commercial property market, the Chancellor heeded calls to intervene on the proposed up rating of business rates, stating in a £6.7bn giveaway (the most costly of the Chancellor’s business tax handouts), that one half of all UK businesses will pay either lower, or no business rates at all while any rates payable will be increased annually from 2020 by inflation as measured by the lower CPI index rather than the planned RPI index. Business rate relief for small companies was raised from £6,000 to £15,000 and the higher rate from £18,000 to £51,000 meaning that 600,000 more businesses would pay no rates.

The lowering of the Office for Budget Responsibility’s economic forecasts for the UK were not a surprise given the weaker outlook for the global economy. Flat growth of around 2% each year for the next six years, following the UK’s recent modest recovery from deep recession is hardly a ringing endorsement of government policies, but despite that, the UK’s performance is likely to prove one of the more resilient of the major economies in the near term. Given these downgrades, the country still faces major challenges in meeting the Chancellor’s target of achieving a budget surplus by 2020. Tighter controls on offsets to global corporates’ profits will assist, as will further spending cuts amounting to £3.5bn by the end of the decade, while the old favourite of Chancellors in need, the further closing of tax loopholes, is expected to generate a further £12bn by the end of the decade.

In a budget for ‘putting the next generation first’, rates of corporation tax were cut, as were taxes on oil and gas exploration and production, in an attempt to assist the beleaguered North Sea oil industry. New powers to tackle VAT fraud by overseas online retailers were also announced.

Personal tax thresholds were raised while the rates of capital gains tax were reduced. And though many thought that the Chancellor would have taken advantage of the low oil price by reinstating the fuel duty escalator, he elected to leave fuel duty unchanged, as were excise duties on beer, cider and spirits. To sweeten savers, the Chancellor raised the ISA limit from £15,240 to £20,000 from 2017 and introduced a Lifetime ISA for savers below the age of 40. The government will contribute £1 for every £4 saved up to a maximum saved of £4,000 p.a. and which is hoped to encourage the young to save, buying a home or for their retirement.