Brexit news

Just a few days ago, Prime Minister Johnson apparently ended negotiations with the EU saying that there was no point carrying on unless the EU fundamentally changed its position. Perhaps a week is indeed a long time in politics as talks are very much back on and it appears that the UK and the EU could now be inching towards a deal. It has been reported that compromises from both sides on one of the thorny issues, that of post-Brexit fishing rights, could kick start discussions that would enable a trade deal to be unveiled before the year end.

The compromise would allow the UK to regain control of its territorial waters while also allowing EU fishing boats access. It is reported that the protagonists are looking at a plan which uses the concept of ‘zonal attachment’ where quotas are determined by the amount of fish stocks on either side’s waters. If a deal is reached, it would allow British fishermen to catch significantly more fish than at present and it would also defer the decision on the amount of the EU quota until after the wider trade deal is signed.

Talks are continuing with both sides accepting that the clock is ticking with some tough negotiations still to come. But the fact that discussions are still ongoing is a welcome development.

Meanwhile the UK and Japan have signed a trade agreement, Britain’s first post-Brexit trade deal. It means that virtually all of Britain’s exports will be tariff free while tariffs of Japanese cars entering Britain will be tariff-free from 2026.

While symbolic, the trade agreement would boost trade between the two countries by about £15 bn – adding less than 0.1 percentage point to the UK’s GDP – a tiny fraction of the trade that could be lost were no deal with the EU be agreed.

Global economy

It is fair to say that we are all experiencing difficult times, perhaps the most challenging since the Second World War; challenges where economic policy alone is insufficient. Many countries are experiencing a ‘second wave’ of Covid-19 cases, testing has been ramped up across the globe and social restrictions are being reimposed; still the death toll rises, still we await a suitable vaccine and governmental spending still spirals relentlessly upward.

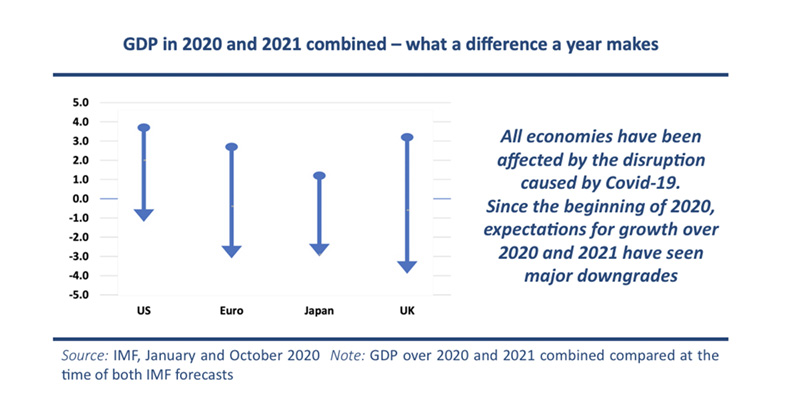

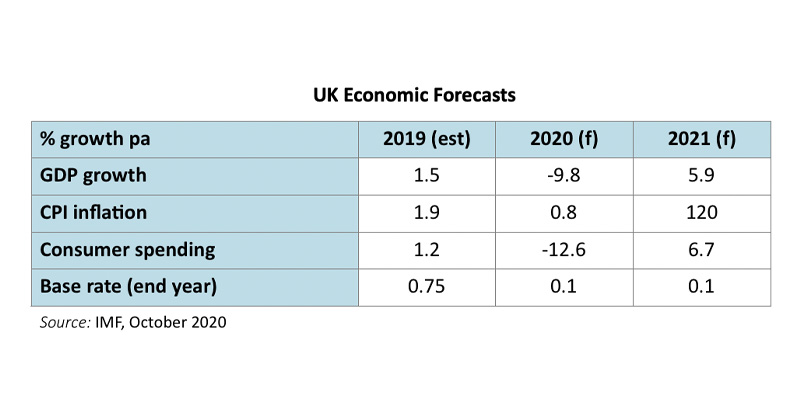

Despite this gloomy environment, economic forecasts for 2020 are generally better than those predicted three months ago, following on from slightly less damaging contractions in the second quarter, but these minor upgrades have been counterbalanced by the expectation of a weaker recovery next year.

The relatively stronger Q2 outturn has been helped by the sizeable, quick and unprecedented fiscal, monetary and regulatory responses that has helped maintain disposable income for many affected households and protected cash flow for businesses. Collectively, these actions have so far prevented a recurrence of the financial meltdown of 2008-10. How governments are going to pay for this largesse is a tetchy question for the future. At least, the probability of low interest rates for a longer period together with the anticipated recovery next year alleviates the debt service burdens in many countries.

While the worst in terms of economic fallout is now, hopefully, behind us, the pace of recovery is likely to be lengthy, uneven and uncertain. Many countries are now facing a second wave of infections, once again putting severe strain on health services and any hope that the illness and its economic impact would be confined to 2020 now seems unlikely. Indeed, the number of new cases in many countries is currently rising at a faster rate than during the initial February – April phase although one has to bear in mind the number being tested now is significantly greater than six or seven months ago. This has caused a further downgrading of the economic outlook for many countries in the near term compared to pre-pandemic expectations.

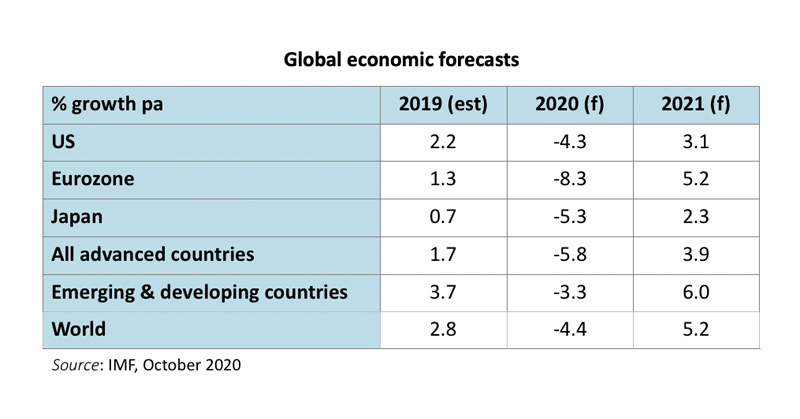

Our global economic forecast for 2020 has improved from -4.9% three months ago to -4.4% with upgrades to our forecasts for the US (by 3.7 percentage points), the eurozone (by 1.9 pp) and Japan (0.5 pp). All these upgrades are followed by slight downgrades next year. The risks remain very much skewed to the downside, most visibly seen in the sudden falls in global stock markets at the end of October when markets started factoring in a much worse economic consequence of the ‘second wave’.

After a partial recovery next year, global growth is forecast to gradually slow to around 3.5% pa in the medium term, somewhat short of the c 4.0% – 4.5% pa anticipated pre-pandemic. The reduction in the growth outlook will hit average living standards and the pandemic will reverse the near three decades of progress in reducing global poverty and will increase inequality, particularly hitting those working outside the formal safety nets.

Nonetheless, the interminable US circus called the election is over – bar the shouting! – for another four years. While not quite overshadowed by Covid news, the election of Jon Biden (subject to potential litigation by Trump) is likely to change many of Trump’s policies, including tax increases for both high earners and corporations. Only time will tell, as will dissecting ex-President Trump’s tenure. Staying in America, though with global ramifications, the Federal Reserve indicated that there would be no interest rate increases until at least the end of 2023 adding that it would not tighten policy until inflation has been “moderately above” 2% “for some time”. Its Chair, Jerome Powell said the statement meant “rates will remain highly accommodative until the economy is far along its recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic”.

The EU economy

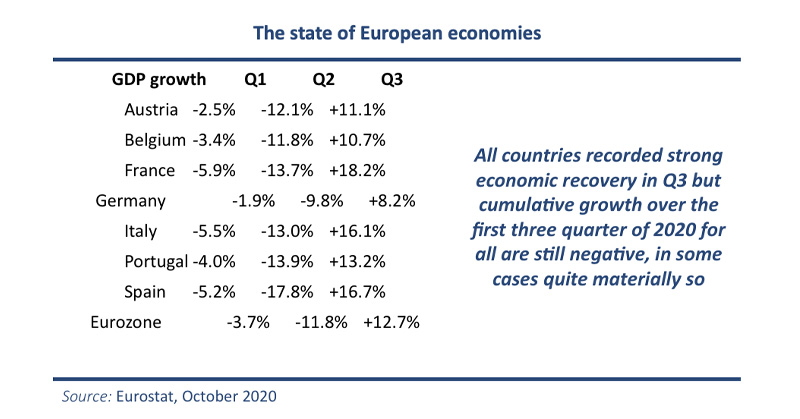

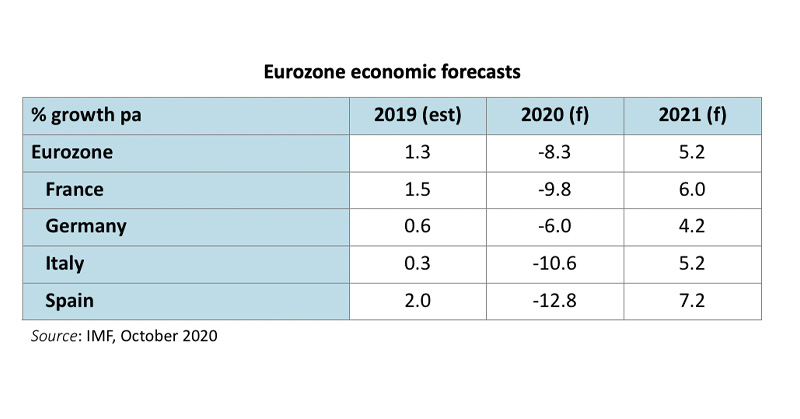

The eurozone and EU recorded a stronger than anticipated recovery in the third quarter, the former posting growth of 12.7%, fully three percentage points ahead of expectations. This followed two quarters of decline which in total had left the zone 15% lower than at the start of the year. But any hope that the single currency bloc could build on this recovery in Q4 have been derailed by new lockdowns or circuit breakers which have been imposed in many countries in recent weeks.

Expectations for Q4 are being reduced with some commentators believing that a double dip – i.e. further contractions in activity – could be on the cards. Certainly, the restrictions re-introduced will have an adverse effect but a slowdown was already being seen. France’s finance minister is on record saying that the French economy will contract by a worse than expected 11% this year. Meanwhile, German consumers are tightening their belts. The boost from the cut in VAT is fading, pushing retail sales down 2.2% in September.

Meanwhile, owing to the job retention schemes that were introduced earlier this year as Covid-19 became established, the rise in unemployment has so far been limited. Over the third quarter, the euro area’s unemployment rate was 8.3%, 30 bps higher than that three months earlier and 80 bps above the rate 12 months ago.

Inflation turned negative in August and at -0.3% in September remains well below the ECB’s target of ‘close to but below 2 percent’. Oil prices have been particularly weak recently as markets consider the financial and economic impact of further lockdowns, and they are likely to remain weak for the foreseeable future putting further downward pressure on inflation.

Our forecasts have been increased slightly for this year but reduced by a small amount next year for most countries. However, with many European countries now in the midst of a tightening of restrictions, there is a real fear that Q4 growth (and consequently for 2020 as a whole) will be significantly lower than that expected.

The UK economy

A 20% contraction in the second quarter was not part of Boris Johnson’s manifesto a year ago, but then, the terms coronavirus and Covid-19 had not yet become part of everyday conversation. Not only was the fall the worst quarterly result in UK history, it was the worst performance by any G7 country, and one of the worst posted in the developed world. With the UK’s record on the number of Covid-related cases also one of the worst, it has not been a 2020 to remember for the government.

Predictably, Q3 saw a major recovery, but momentum has since stalled as the virus reasserts itself in the community forcing significant tightening of the economy. The magnitude of the recovery remains uncertain, with the first, flash estimate expected later in the November. Expectations for Q3 growth range from 13% to 18%. Hopes for Q4 have been lowered in line with other European countries and another contraction cannot be ruled out. It is likely that the full year outcome will be a decline of around 10%, by far the worst outcome seen since the immediate aftermath of the Great War but similar to other countries in the continent.

Meanwhile, the furlough scheme, which pays workers affected by the forced, temporary closure of businesses, and which was due to end on 31 October and be replaced by a less generous job support scheme, has been extended until March 2021, meaning that the scheme will have been in place for 12 months. Around 9.6 million workers have benefited from the scheme since its start this March at a cost to taxpayers of £40bn.

Unemployment has also risen to its highest level in over three years as the pandemic continues to hit the economy. The unemployment rate increased to 4.5% in the quarter, up from 4.1% in the previous quarter. Similarly, the number of redundancies in the last three months increased to 227,000, the highest since 2009 in the midst of the financial crash. These statistics are not as bad as were initially feared at the start of the hiatus when talk of an increase to an unemployment rate of 9% was rife. But with the second wave of infections now upon us, further and significant job losses are likely.

With the pandemic no nearer to its conclusion and its financial impact no nearer being finalised, the Chancellor has taken the sensible step of postponing this year’s Autumn Budget. ‘… now is not the right time to outline long-term plans – people want to see us focused on the here and now,’ the Treasury said. That means that the difficult decisions on how the cost of fighting Covid is to be financed has been deferred into the new year.

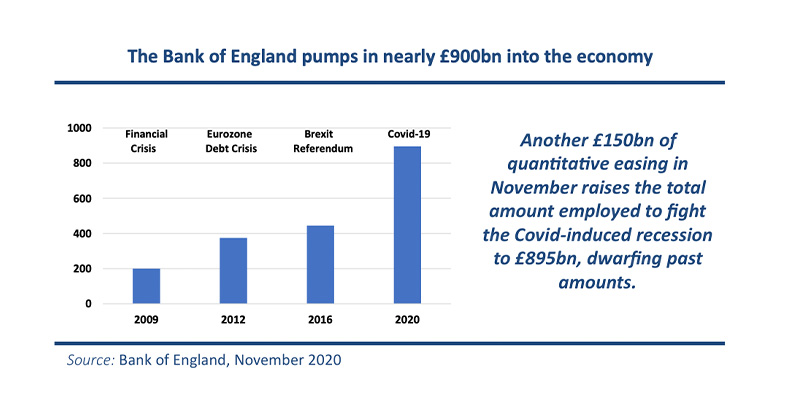

On the day lockdown restrictions were imposed in England, the Bank of England announced another £150bn of quantitative easing, taking the total employed this year to £895m, dwarfing the amounts utilised in the past decade. The Bank acted as it was concerned that the UK would enter another downturn as the new restriction hinder the recovery. Interest rates were kept at their record low levels, 0.1%.

This second period of lockdown in England should not be as damaging to the economy as the spring one was for several reasons: presently, the period of lockdown indicated is only four weeks as opposed to the uncertain period when the first lockdown was announced in March; unlike the previous period, manufacturing, construction, real estate, schools and universities, nurseries and garden centres are allowed to open. The four-week lockdown is due to end on 2 December, and that therefore affords the possibility of a re-opening in the run-up to Christmas which would obviously be of major benefit to retailers. Additionally, lessons have been learned both from communications and working from home. All that should point to a less damaging impact to the economy in December than what happened earlier in the year.

Summing up, the economy has made a strong recovery in Q3 but momentum has slowed in recent weeks pointing to a weak Q4. As the Covid case numbers remain elevated, a fresh lockdown across much of the UK will further hinder growth while it is likely that the economy will not reach its pre-Covid level until 2022. Meanwhile, the cost to the Treasury keeps mounting. How the Chancellor tells us how we are paying for the unprecedented measures introduced over the last eight months has been deferred until next year.

Market Commentary

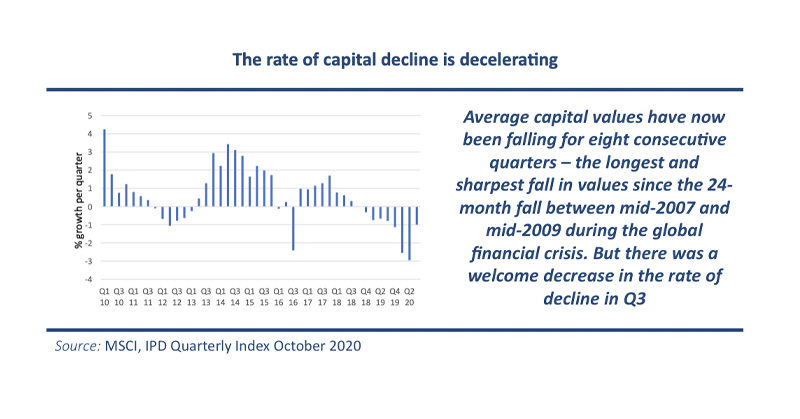

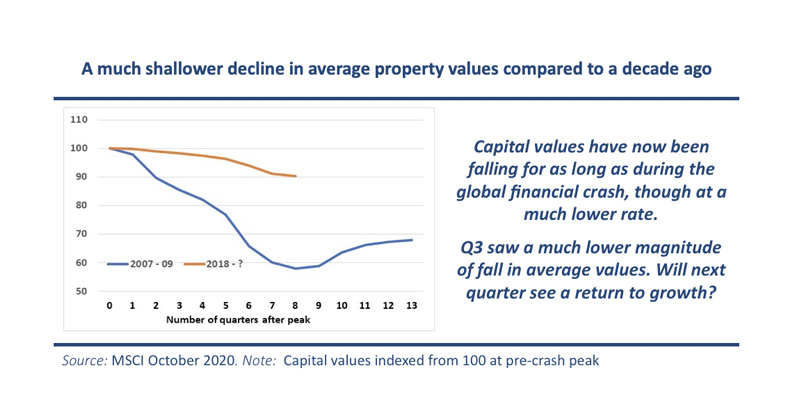

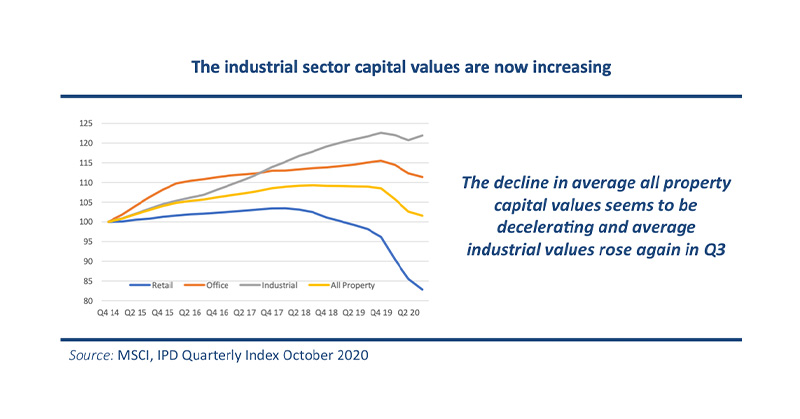

A 1% fall in average property values over Q3 took the cumulative fall in values to 10%. This period of declining property values started two years ago, making this decline of similar length of time to that over which values fell during the global financial crash. Perhaps the same duration, but thankfully, not the same magnitude, as average values fell a whopping 44% a decade ago. But whereas property values started to rise two years after the decline started in 2007, there are few signs of respite in the current collapse. However, the 1% fall in Q3 was significantly less severe than in the two previous quarters and gives hope to the belief that the end of the decline may be near. Much will depend on the strength of the economy in the coming months.

While most areas of the market are witnessing falls, it is the retail sector which is bearing the brunt. Once again, the shopping centre segment was the worst performing over the quarter, falling in value by 6.6% for a cumulative fall of 24% this year alone. The fate of standard shops was not much better, seeing a 3% fall in the quarter. Neither segment was helped by the news that the number of shop units closing in the first six months of the year hit an all-time high with 6,001 closures, up from 3,509 in the corresponding period last year.

It is not all doom and gloom on the high street, though. There are a few bright spots too, as there is a steady flow of openings. For example, consumers are rediscovering their local retailers while there has been a mini boom in takeaway and pizza delivery shops. Additionally, there is rising demand for services such as tradesmen’s outlets, building products and locksmiths. These new units, welcome though they are, however, are dwarfed by the numbers closing. There is still a lot of pain to come for the retail sector; a lot of corporate restructuring and many more redundancies to come, despite the Chancellor’s laudable efforts on job protection.

From a performance measurement point of view, institutions, which are most likely to favour investment in city centre retailing units, are often not represented in neighbourhood shops and parades and so it is debateable whether valuation upticks in these local shops will work its way into the MSCI (IPD) indices.

One of the success stories this year has been the growth of internet sales, though that of course has had negative implications for the high street. As retailers have been augmenting their online presence, there has been significant growth in retailer interest in distribution warehouses and also investment by these retailers in the final part of the supply chain known as the ‘last mile’. This is fuelling growth in these smaller distribution warehouses in suitable locations nearer the customer. It is no surprise that these parts of the commercial property market are presently the strongest. Average industrial values bucked the recent trend in Q3, posting an increase of 1.0%, the only sector to show an increase, with the sector back in growth after six months of decline.

From success stories to failure! Business recovery firm Begbies Traynor claims that there are now over half a million firms in ‘significant distress’. Needless to say, the biggest increases in struggling companies came in food retailers, construction and real estate and property sectors. And that number could be even higher if courts were operating normally, as the number of county court judgments and winding up provisions are lower as winding-up petitions for Covid-related debts are currently banned. That has led to concerns that, once these restrictions are lifted and Government support is removed, the number of firms going bust could surge as a ‘brutal reality check’ hits the UK economy. Many of these companies are surviving only through the availability of Government loans and employee cost subsidies, but once these come to an end, there will be little hope for many of them.

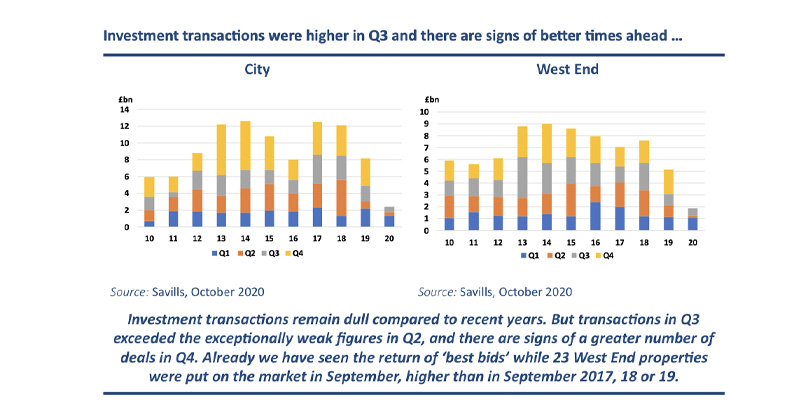

Investment transactions were notably higher in Q3 than in the depressed second quarter. Total deals in the country totalled £6.5bn (source: LSH), almost 50% higher than in Q2 but still 50% lower than the five year quarterly average. September accounted for over 40% of Q3 deals, perhaps indicating that the market is now beginning to pick up after weakness over the spring and summer.

Surprisingly, investment activity was driven not by London but by provincial deals, where the volume of deals was down only 28% from its quarterly average. This compares with a 50% reduction in central London office transactions. Offices were the most favoured sector in the quarter where deals amounted to £2bn were recorded: industrial properties also remained in vogue with deals worth £1.9bn transacted in the three months while retail assets were again out of favour with less than £1bn transacted for the fourth quarter in a row.

Although activity was relatively muted in London, it was home to the quarter’s largest transaction, the purchase of Morgan Stanley’s headquarters in Cabot Square, Canary Wharf for £380m. The purchaser was a Hong Kong-based REIT. The next two biggest transactions in the quarter were also offices – Sun Ventures purchase of 1 New Oxford Street for £174m and Tristan Capital’s £120m purchase of Reading International Business Park. As debate continues as to the future of offices in the post-Covid world, these purchases are major statements by the purchasing funds concerned.

Summing up, the property market enters the winter season in much better shape than at any time since the outbreak of the pandemic earlier this year. Take-up and investment statistics remain dull, but are on an upward trend following extremely weak figures over the summer. Anecdotal evidence of the amount of lettings and investment transactions also points to an improvement in the final quarter of the year. But perhaps the most positive feature to emerge over the course of Q3 was the sudden slowdown in the rate at which average property values are declining. The rate of decline in property values had been accelerating for four successive quarters. The outturn for Q3 was significantly better than those recorded over the previous two quarters and gives a glimmer of hope that the two-year decline in property values may be near an end. Whether that is the case will largely depend on the state of the economy, whose outlook is as confusing as ever. Not only do we have potential lockdown-induced weakness but we also have the ‘deal / no-deal’ discussions with the EU. It will be an interesting couple of months.

Central London offices

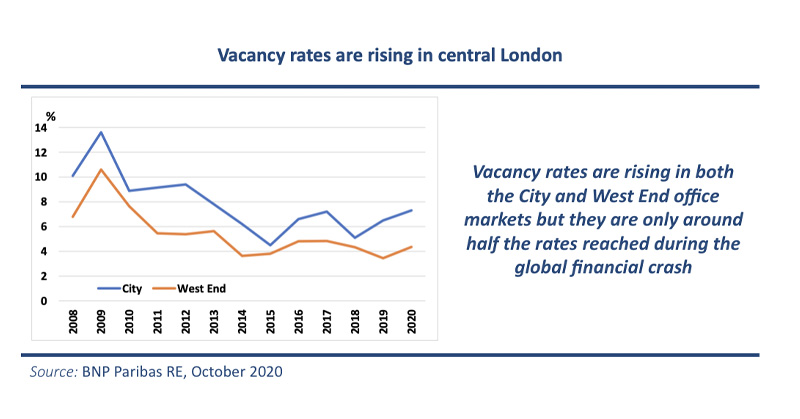

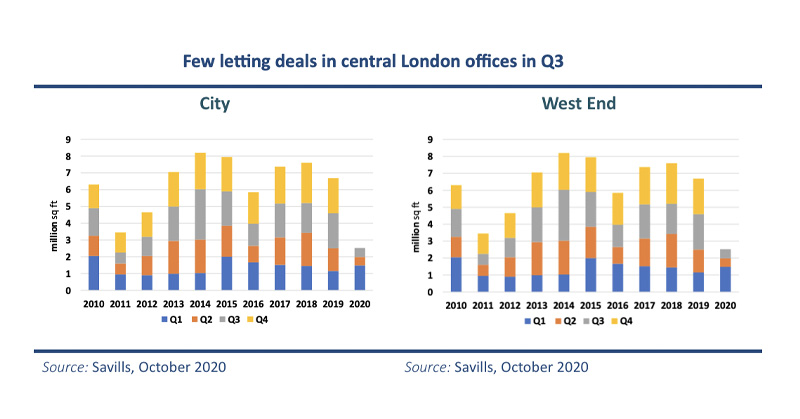

With the economy struggling to regain momentum, it comes as no surprise that take up of central London office space currently remains muted, although Q3 was stronger than in the almost moribund second quarter. Vacancy rates have been rising over the course of the summer for three reasons: below average take up, the fact that new Q1 2021 completions now come into the equation and from a significant increase in tenant marketed space.

In the City and West End combined, the amount of tenant released space available for sub-leasing increased by over 1m sq ft to almost 4.9m sq ft over the course of the quarter. This amount is three times that available before lockdown and now accounts for one-third of the total amount of space available in central London. With many businesses facing unprecedented uncertainty over their futures, it can be expected that this space will continue to grow in the coming months.

Overall take up is recovering from its earlier slumbers with September figures for the City and West End showing welcome improvement from recent months. That said, though, cumulative take up for both Q3 and for the first nine months of the year remain well below recent comparables. At just over 500,000 sq ft, the City take up in Q3 was the lowest Q3 for 16 years, while the West End take up, at just under 400,000 sq ft, was the lowest third quarter lettings this century.

Confidence in the investment market is also slowly but surely improving. Total investment deals across the two central London office markets in Q3 amounted to £1.27bn, double that of the previous quarter, although it is still way below pre-Covid levels. The acquisition of 1 New Oxford Street at a yield of 4.2% has already been referred to, but that was eclipsed as the largest deal in the quarter by the purchase of the Morgan Stanley headquarters in Canary Wharf for £380m. Both strong statements as to the future of the office post Covid.

Capital values are still under downward pressure, but the rate of decline in Q3 was less than in the two previous quarters. Average City values fell 0.5% while those in the West End by 1.1%, bringing the cumulative fall this year to 1.8% in the City and 3.6% in the West End. Rents, though, are faltering. Prime City rents, at £77 per square foot in September are 4.6% lower than three months earlier and 12% lower than 12months ago. West End prime rents remain around £100 psf.

Summing up, the central London office market has weathered the recent storms relatively well. Take-up and investment transactions are recovering though still well short of recent levels. While many of the statistics are moving in the right direction, the increasing amount of tenant marketed space is a worrying development. Central London offices are still vulnerable to the failure of the Brexit discussions and to the debate over the future role of offices versus home working. In the short term, further weakness in rents is likely.

All investment and take up data and statistics from Savills, unless stated; all performance statistics from MSCI; all graphs by the author.

Stewart Cowe, November 2020