Brexit news

Brexit-weary Britons received an early Christmas present with the announcement that the UK and the EU had finally agreed a trade deal. Despite both sides threatening to abort the talks during the last few, frenetic weeks, the deal was finally signed by both parties on 30 December. The EU has made a habit of dragging out negotiations to the wire – recall the Greek bail out and more recently, the €750bn “Next Generation“ recovery fund – this time, both sides left it almost to the closing minutes before announcing that agreement had been reached.

While Prime Minister Johnson claims that “Brexit is done”, the reality is far from that. The deal only involves the importing and exporting of goods, and does not cover, for example, financial services, which account for a sizeable percentage of Britain’s workforce and trade with the EU. Even the Prime Minister acknowledged that the Brexit deal “perhaps does not go as far as we would like” for financial services. It is hoped that a co-operation agreement will be signed by the two parties on financial services by March. Going by past experience, any deal is unlikely to be ratified soon.

Even though the trade deal is now in force, ensuring that goods flowing between the two regions are free of tariffs, companies have not been finding trade as frictionless as before. Bureaucracy has increased significantly resulting in delays on both sides of the channel, and evidence is appearing that some foodstuffs are having to be destroyed owing to the delays in arriving at the end user. Whether these features will be ongoing issues or merely teething troubles will only become evident in the coming weeks and months.

Over the course of 2020, Britain signed more than 50 trade deals with countries outside the EU, but one that failed to be completed was one with the United States. It had been anticipated that signing a trade deal with the Trump administration would have been easier and quicker than with any future president, but no deal emerged. President Biden no doubt has far more in his in tray at present than concerning himself with the relatively small matter of a trade deal with Britain.

One potential trade deal that may be announced soon is that with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP-11) which is the recently agreed trade agreement between 11 Pacific rim countries. While the population of these countries totals 500 million, or roughly 10% larger than the EU, they account for less than 9% of Britain’s trade.

Global economy

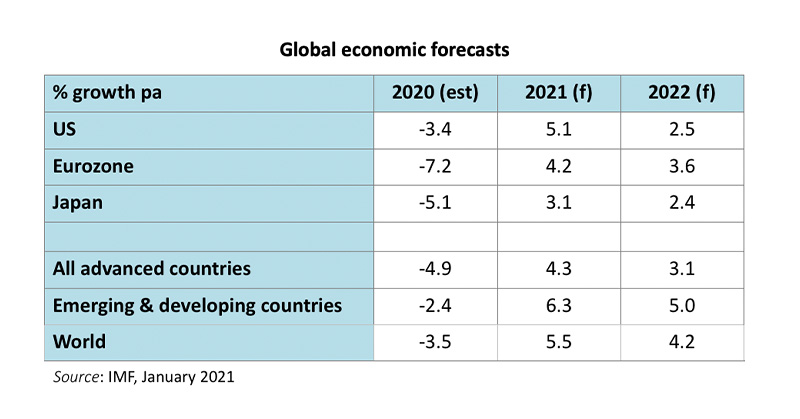

Following on from somewhat higher rates of activity in the second half of last year, our expectation for global growth in 2020 has been raised by 90 basis points from our -4.4% forecast three months ago to -3.5%. This outturn would have been even better had many countries not been in some form of lockdown in Q4, caused by a further wave of Covid-19 infections and more worryingly, new and more easily transmittable strains of the virus.

However, 2021 began with the news that vaccines have been approved for general use and that the vaccination rollout is progressing in many countries. This fact alone has brought about improvements to our global activity forecast for this year, increased by 30 bps from October’s 5.2%. The outlook for next year is unchanged at 4.2%. The availability of the vaccines is the prime reason behind the belief that downside risks to our forecasts are now lower than for some time.

The improvements to the forecasts are not evenly spread; much will depend on the ability of countries to source and pay for the vaccine. Aside from the boost given by the vaccination programme, the upgrades reflect government spending measures, particularly in the US and Japan, which see cumulative upgrades of 160 bps and 150 bps respectively over 2021 and 2022 combined. In contrast, Europe’s fortunes have been reduced by a total of 50 bps over this year and next.

Q3 growth mostly surprised on the upside. Private consumption rebounded strongly but in contrast, apart from in China, investment has been slower to improve. The momentum behind the strong Q3 numbers, however, has not been carried on to Q4. Rising numbers of cases in many countries plus the consequent lockdowns imposed have stalled, at best, this recovery. With lockdowns still in place, there are fears that many countries will face a further recession, reporting declines in GDP in both the final quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021.

Vaccinations aside, a lot still has to be done on the economic front to limit permanent damage from the severe contraction in activity last year. The two-year forecasts assume that the vaccination programmes are rolled out by mid-2021 for most advanced countries and by the second half of 2022 for most other countries. Together with improved testing and tracing practices, transmission of the virus will be brought under control everywhere at low levels within two years. This year sees further huge fiscal support in the US, Japan and the EU, while fiscal deficits should decline in most countries as revenues increase and government spending falls with the recovery. Additionally, financial conditions are expected to remain supportive for some time.

The Q4 GDP reporting season got off to an upbeat start with the US announcing a better than expected annualised growth of 4%, although that was down significantly from the rebound seen in the previous quarter. Over 2020 as a whole, the US economy shrank by 3.4%, the sharpest fall since 1946. It is likely that the US will have performed better than most other major economies in both Q4 and over 2020.

With the Democrats now in control of both houses in Congress, President Biden appears to have a clear mandate to implement fresh policies and indeed to reverse some of his predecessors’. Raising the minimum wage and paying higher Social Security payments are key policy changes which should drive household consumption, the “Buy American” laws will seek to protect and boost jobs, while the US pledges to re-engage with the Paris Climate Accord.

The EU economy

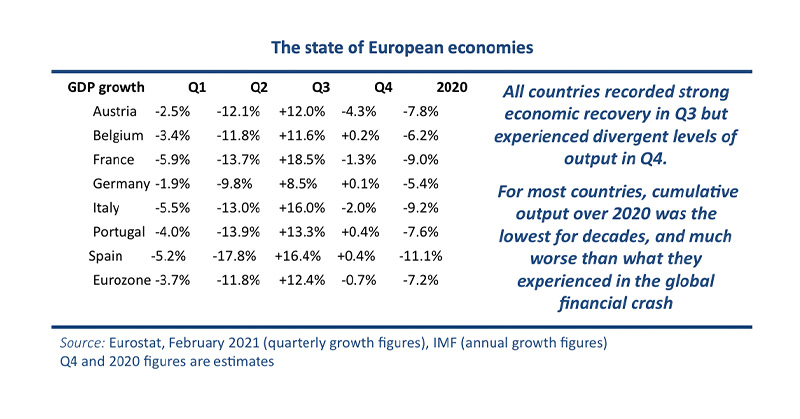

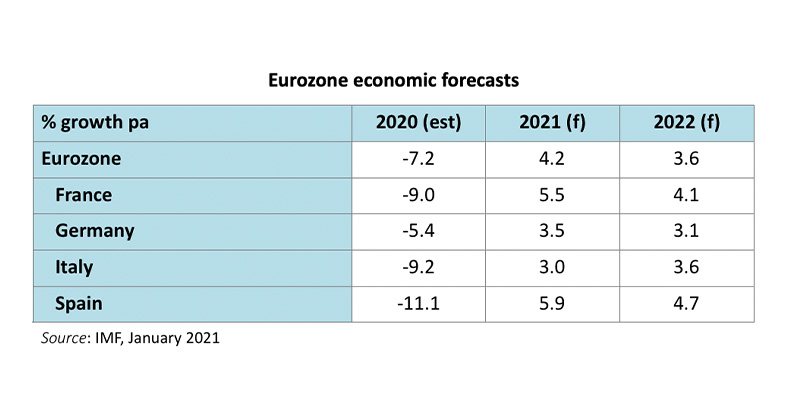

Most countries performed better economically than anticipated during Q2 and Q3 enabling us to up our forecast of activity for 2020 as a whole by 110 bps. However, lockdown measures across many continental countries towards the end of last year has prompted a downward reassessment of activity in Q4 and the start of 2021 and has resulted in trimming our full year estimate for the year by 1 percentage point to +4.2%. These changes confirm that the single currency bloc will suffer a permanent loss of output resulting from the pandemic. Indications currently suggest that the eurozone will not recover its pre-Covid level until late 2022 or early 2023. This recovery, though, will not be uniform across the 19-nation bloc, nor uniform across sectors.

Policy responses by the European Central Bank and individual countries have certainly cushioned the impact of the pandemic, though the 7% – 8% estimated contraction for 2020 is by far the worst annual figure in the short life of the eurozone. Individual countries have seen a wide divergence in activity, ranging from the almost euphoric outcome of just a 5% contraction in Germany to the much greater losses experienced in the more tourism-focussed countries of southern Europe.

The eurozone has the luxury of ultra-low interest rates. Consequently, member countries and the European Central Bank enjoy low borrowing costs which is a major benefit at a time when debt levels for many are at elevated levels. With inflation expectations also muted, monetary policy can remain supportive until the recovery takes hold.

Despite the job retention schemes that were introduced last year, unemployment has been rising across the continent. The number unemployed in the euro area at the end of the year has increased to 13.67 million or 8.3% of the working age population, an increase of 1.5 million in the year. The similar figures for the EU as a whole are 16 million unemployed, up almost 2 million in the year or a rate of 7.5%.

The UK economy

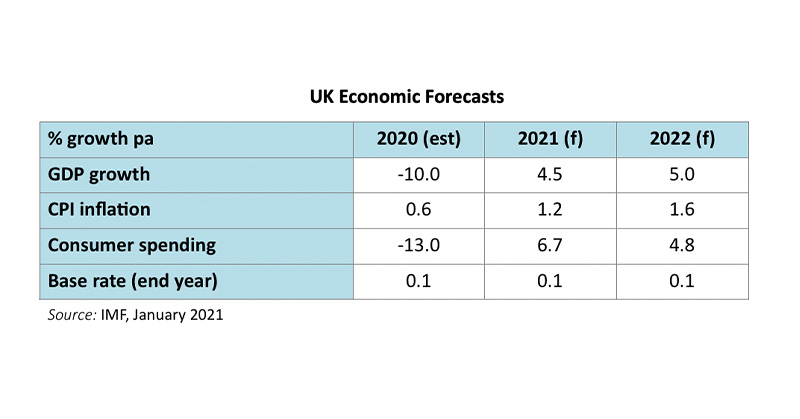

Economic modelling at the outset of the pandemic last year anticipated a deep but relatively short downturn in the first half of the year followed by a strong rebound in the second half. While the downturn generally fell in line with expectations, the recovery has somewhat stalled owing to the emergence of further, more easily transmitted forms of the disease. Activity in the UK failed to build upon a solid recovery in the third quarter, with strict lockdowns being imposed before and after Christmas resulting in yet more pain for retailers and the likely creation of a double dip recession.

2021 is going to be a battle between the fast-spreading virus and the optimism that the Covid-19 vaccine rollout will allow life to get back to some sort of normality. But the current downturn indicates that activity will not regain its pre pandemic level until sometime in 2022. The arrival of the vaccine has at least limited further downside risks but we are anticipating that the economy will still only claw back roughly 40% of the estimated 10% 2020 decline this year.

The travails of the retail sector have been a regular feature of this report over the last few years … and with good reason. Retailers suffered their worst annual sales performance on record last year, driven by a slump in demand for fashion and homeware products. While food sales were 5.4% ahead of the 2019 amount, non-food sales fell about 5%, according to the British Retail Consortium.

It therefore came as no surprise that job losses in the retail industry hit another high last year with a loss of almost 180,000 jobs (source: Centre for Retail Research). There is not expected to be any respite this year either, with the trade body expecting another 200,000 jobs to disappear. But while the retail sector has been at the forefront of job losses during the pandemic, it is important to realise that it is not only the retail industry undergoing rationalisation. The fact that unemployment has risen by over 400,000 (source: ONS) since the beginning of the crisis highlights that it is not just retailers that are suffering.

Many leisure and hospitality ventures are struggling to cope with enforced closure and apart from the retail industry already mentioned, it is these sectors of the economy which are likely to suffer most in terms of job losses. Some pain has been deferred owing to the furlough schemes and other help provided by the government, but many of these, previously vibrant parts of the local and town communities, will be lost for ever.

The new year could not have begun with more sobering news that two of the high streets’ most established retailers, the Arcadia Group (owner of brands such as Top Shop and Top Man) and department store Debenhams are both going to disappear from town centres. Both companies fell into administration last year, and although the Debenhams brand and brands within the Arcadia stable have been bought by online specialists ASOS and Boohoo, neither purchaser intends keeping a high street presence. This means that over 25,000 jobs will be lost in the closure of these previously former giants of the high street.

On the brighter side, there is certainly evidence that there is a significant weight of money waiting to be unleashed into the economy when the tide turns, the vaccination programme completes and the economy returns to some sort of normality. With Britons having had limited spending options over the last year, many families will have accumulated greater than usual savings thereby offering some hope to the beleaguered retail sector. Some estimates put the amount of excess savings over the last nine months at £150bn, a figure that could grow to £200bn by April. But averages do hide the darker side to the effects of the pandemic. The Office for National Statistics has indicated that almost 9 million people had to borrow more money last year just to “get by”. Many of these individuals were young and low earners, both groups suffering more from furloughing and job losses.

In economic terms, Britain suffered a particularly bad 2020 compared to many of its peers. Reasons given by commentators for the country’s underperformance include the greater weight of the country’s service sector and Brexit uncertainties. But a report from Capital Economics argues that the UK population fell by 1.4m workers last year – primarily on account of migrants electing to return home (for either virus, job or Brexit-related reasons). Whether these workers return could have a significant bearing on activity this year.

Market Commentary

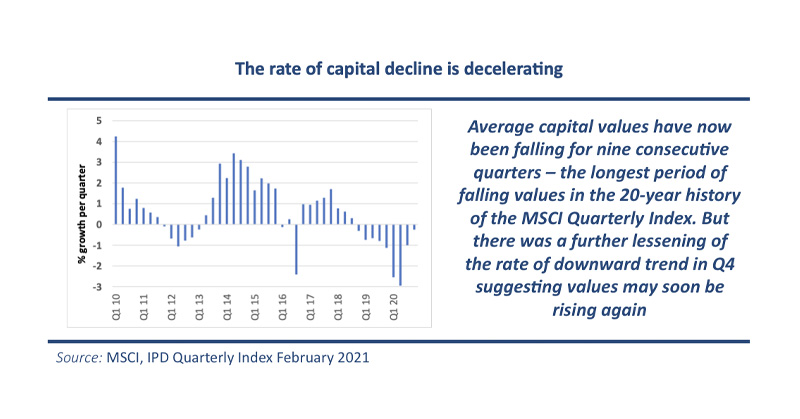

Average property values fell again in Q4, extending the period of decline to nine quarters, the longest in the 20-year history of the MSCI/IDP Quarterly Index. The 0.25% decline was the lowest quarterly reduction in that nine-quarter period and continues the trend of reducing declines which prompts hope that capital values will soon start rising.

With the two previous quarterly results showing a narrowing of the extent of capital value falls, there was some expectation that Q4 could see a reversal of this lengthy negative trend, the possibility of which being heightened when both the recent MSCI Monthly Index and the CBRE Index showed gains.

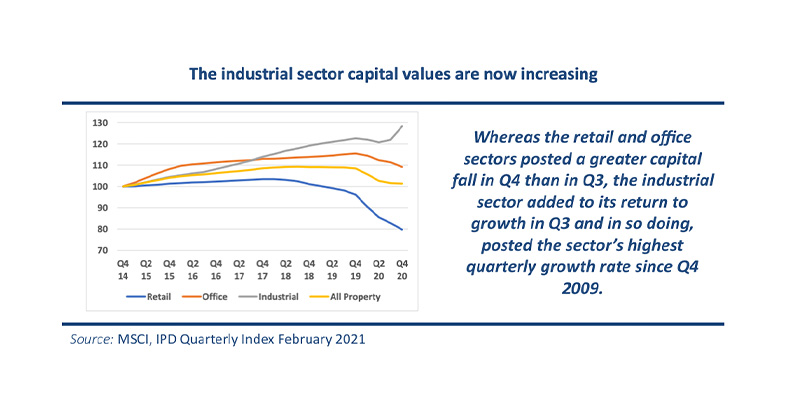

However, unlike the period of declining values around the global financial crash (GFC) when average values in each of the three sectors fell by roughly similar amounts, the magnitude of the valuation falls this time has been more sector specific. The polarisation of valuations of, on the one hand, industrial assets, and on the other, retail assets has been stark. The Q4 quarterly total return differential between the total returns of the best and worst sectors, i.e. industrial and retail, is the widest ever recorded.

Since September 2018 (the recent peak in market valuations), average industrial values have actually risen by almost 6%. By contrast, average retail values have fallen by a massive 23%. Indeed, the collapse in retail values started much earlier, its peak in terms of average valuations being the end of 2017, and the fall in average retails since then has been 30%. Shopping centres have fared even worse, having fallen on average by 50% over that period. Given the continued bad news emanating from the retail industry, there is no sign of a quick end to the constant falling valuations.

Offices, historically the most volatile sector, have been the model of consistency recently. Over the last two years, average values have been trimmed by just 5%. Central London offices have shown divergent paths, City offices down just 1% and West End by 6% over that period. Given both Brexit and pandemic issues, either of which could have proved detrimental to both sentiment and occupier demand, these performance figures are particularly robust.

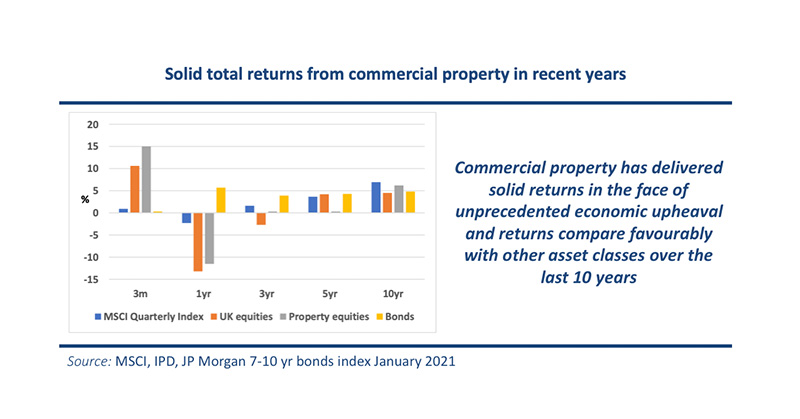

In total return terms, commercial property delivered a positive return of 0.9% in the fourth quarter and a return of -2.3% over 2020 as a whole. Both figures can be deemed more than acceptable, given the unprecedented shocks to the economy during the year. As can be seen in the next chart, property returns have more than held their own against other assets over the last 10 years. Much of the reason behind commercial property’s solid returns are down to the huge quantitative easing programmes which has inflated real asset prices and the absence of major development recently.

Q4 benefited from a reversal of recent trends by the return of yield hardening in provincial offices and in the industrial sector, although yields still continued their outward yield drift in the retail sector. Yield hardening was noticeably prevalent in industrials, accounting for most of the sector’s average capital value growth of 5.2% in the quarter.

The lower rate of decline in average property valuations is in stark contrast to the events of a decade ago. During the GFC, and over an eight-quarter period, average commercial property valuations fell by 44%; this time, average valuations have fallen by 10% over the last nine quarters.

The changing UK commercial property landscape is clearly illustrated by the real estate investment trust (REIT) market. Currently the largest stock by a large margin is Segro with a market capitalisation of over £11bn – a valuation greater than the combined market valuations of Land Securities and British Land, two previous giants, but whose market caps have tumbled in line with the valuations of their assets. Segro, a specialist in the industrial market, has seen its valuation soar as online shopping has taken off and the values of its predominantly industrial assets have risen. It is reckoned that every extra £1bn spent online last year required almost 1m sq ft of distribution space. And in another chilling reminder of the power and reach of Amazon, the internet giant leased a quarter of the 50m sq ft of warehouse space let in the UK last year.

The outperformance of industrial properties plus strong demand for industrial units have pushed Segro shares to a premium rating (over its net asset value), compared to the deep discounts of the more general trusts.

In contrast to the positivity surrounding industrial assets, retail assets continue their downward trend. 2020 was the worst year for job losses in more than a quarter of a century with an estimated 176,000 retail jobs lost and this year has begun with equally grim news. As mentioned earlier, the collapse of Debenhams and Arcadia will see their shops disappear from the high street, adding yet more vacant space to struggling town centres, and making another 25,000 workers unemployed. In terms of finding new tenants for these soon to be vacant units, it is worrying that a quarter of the former BHS stores, which went bust over four years ago, are still lying empty (source: Local Data Company, August 2020). At this stage of the evolution of the retailing landscape, it is difficult to see where alternative retailing tenants will come from. Landlords and local authorities alike are going to need the wisdom of Solomon to address this thorny issue.

A fall of 3.7% in the last quarter of the year brought the full year valuation fall of average retail assets to 17% while shopping centres fared even worse with a quarterly decline of 8.6% and a full year fall of 30%. The retail market has been hammered by the various lockdown restrictions but Covid was not the sole reason for the collapse in valuations. The industry has been undergoing a structural change for several years, the Covid crisis merely accelerating these changes.

The shopping centre market has been particularly hard hit. Some are questioning the future of these city-centre and edge of town centres. Not only have values been declining, so have investment transactions. Over the course of 2020, only £340m of shopping centres were traded (source: Knight Frank), around one-tenth of the long-term annual average. Of that, only five centres valued above £20m were traded. However, active players in this market appear to be some local authorities who are prepared to bring forward regeneration plans or bring ownership from cash-starved owners to the wider benefit of their towns.

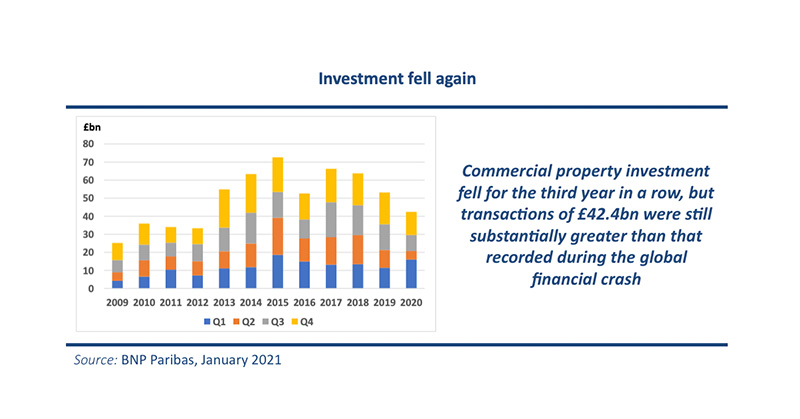

Investment in commercial property fell 20% last year to £42.4bn, the third consecutive year of decline. While Covid-related restrictions on viewing were certainly one factor in the decline, one must not lose sight of the fact that, with few alternative investment opportunities presenting themselves, many institutions are reluctant to part with property assets without first having sourced a replacement. Hence the supply of suitable product on the market fell.

Investment in commercial property fell 20% last year to £42.4bn, the third consecutive year of decline. While Covid-related restrictions on viewing were certainly one factor in the decline, one must not lose sight of the fact that, with few alternative investment opportunities presenting themselves, many institutions are reluctant to part with property assets without first having sourced a replacement. Hence the supply of suitable product on the market fell.

Office and retail sector investment was down sharply last year but demand for industrial product increased 11% from its 2019 total to £8.5bn, equating to 20% of total transactions.

Summing up. The property market enters 2021 in remarkably good shape given everything that has been thrown at it. Against other asset classes, it remains good value and with the rate of decline in property valuations perhaps now nearing its conclusion, the prospects for much of the market looks favourable. We believe that commercial property will remain good value as long as interest rates remain low and the supply/demand equation remains in equilibrium.

Continued growth of online sales is the key driver for industrial/distribution units; rental growth is likely to continue as long as supply remains limited.

In contrast, the retail sector is likely to see continued pain. There seems to be no end to the bad news coming out of the high street but hopefully, once the vaccination programme is rolled out in the coming months, retailers will benefit from the spending spree that many economists predict.

It is the office sector which still divides opinion. On the one hand, rising investor interest and take up point to better times ahead: on the other, rising vacancies, development completions and tenant released space suggest caution. Add to that the uncertainty about the future place of the office in the post-Covid world.

Central London offices

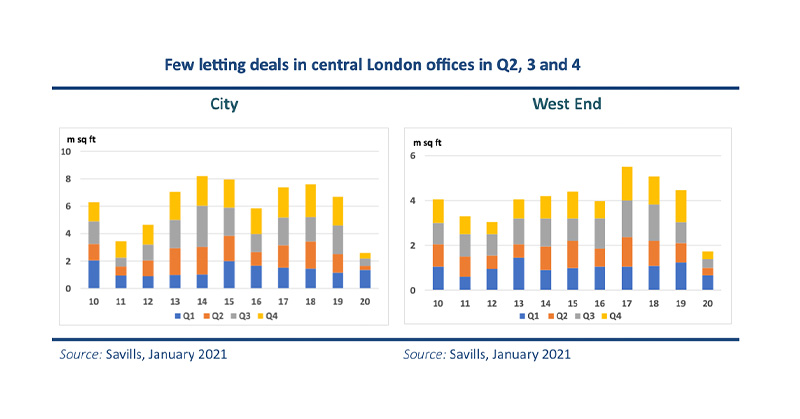

Central London office take up increased over the closing months of the year, but, overall, 2020 turned out to be the worst for almost 20 years. The City take up in the first, pre-Covid quarter of 2020 exceeded the amount leased in the following three quarters. The West End did not fare much better in terms of the amount let, although a healthier closing quarter took the annual amount let to 1.70m sq ft. City and West End take up combined totalled 4.33m sq ft in the year, both sub markets down 60% from the total of the previous year.

Indeed, Knight Frank state that the office leasing activity over the whole of London recorded its two lowest quarters ever in Q3 and Q4. But London is not alone in posting poor letting figures. Both Paris and New York also recorded their two lowest ever quarters for letting last year, albeit having let more space than London in these quarters.

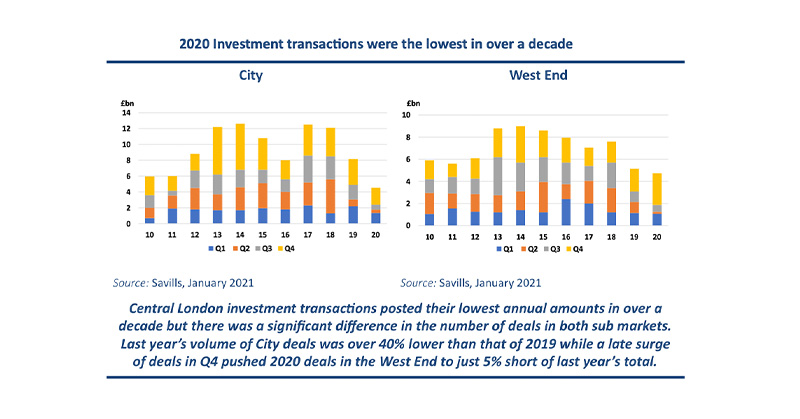

In terms of investment transactions in Q4, City investment of £2.14bn was down by a third on Q4 2019. Meanwhile the West End recorded its highest Q4 investment, £2.87bn, since 2014. It was notable that Land Securities and British Land took the opportunity to sell major London offices in Q4 for a combined £960m. Both purchasers were overseas investors.

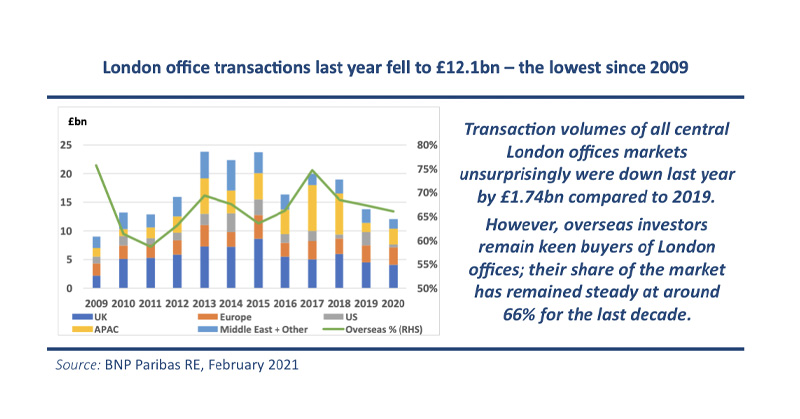

Across all the London office markets, total transactions amounted to £12.1bn, down 13% from 2019’s total and the lowest annual figure since 2009. It is notable that, despite all the Covid-related difficulties in the market, overseas investors remain positive on UK property in general and central London offices in particular. Over the last decade, the overseas share of transactions in this market has remained in a relatively tight band around 66%, peaking at 75% in 2017 and falling to a low of 64% in 2015. The share that overseas buyers accounted for in 2020 was 66%, down 1 percentage point from the 2019 figure.

Investors remain risk averse, preferring properties offering secure, long dated income. Over 80% of City purchases fell into the ‘core’ or ‘core plus’ category last year, while equivalent figures for the West End are similar.

With lettings down, it comes as no surprise that vacancy levels are increasing. Voids increased sharply over the course of 2020, the City’s vacancy rate of 9.3% being the highest in eight years while it is ten years since the West End last recorded a vacancy rate as high as 5.75%. The one positive aspect of the lengthy restrictions in force for much of last year was the fact that many developments are facing delays to completion.

Developments alone do not tell the full story about the extent of vacant space. Across central London, the amount of tenant released space available for sub-leasing increased substantially over the course of 2020. At the start of the year, tenant controlled vacant space was estimated at 1.7m sq ft. By the end of the year, it had risen to over 6.2m sq ft, accounting for over a third of all vacant space. With many businesses facing unprecedented uncertainty over their futures, it can be expected that this space will continue to grow in the coming months as some occupiers seek to reduce costs.

Capital values are still under downward pressure, but Q4 saw a marked divergence in the rate of decline in the sub markets. While average City offices fell in value by just 0.4%, for a 2.2% fall in the year, average West End offices had a much greater fall of 3.5% in the quarter, and a 7.0% fall over 2020. Last year marked the fourth successive year that average City office values outperformed their West End neighbours. Given the West End’s lower vacancy rate and the traditionally wider occupier base, that is an anomaly that could be soon reversed.

Summing up, the central London office market has weathered the recent storms relatively well. Although take-up and investment transactions are picking up, they remain well below recent years’ figures. Of more concern, though, in the short term, is the growing amount of vacant space, which is made worse by the flood of tenant space coming to the market. Central London offices, like all office markets, are still in the midst of the debate over the future role of offices versus home working. In the short term, further weakness in valuations is likely.

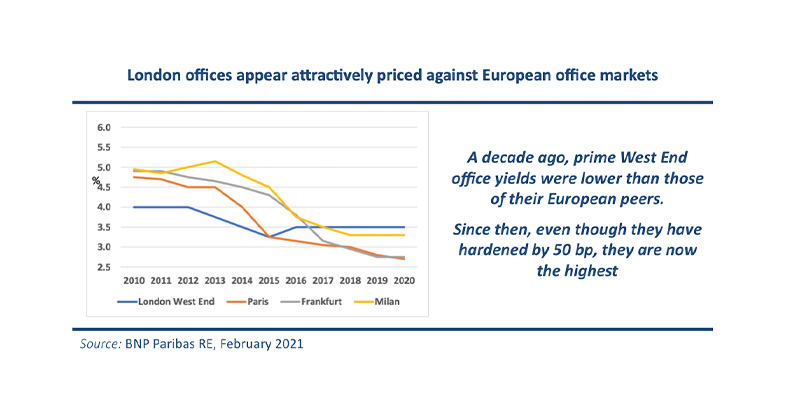

Finally, it is worth considering the wider picture. Most commercial property markets, and certainly those in western Europe, are experiencing not dissimilar features such as lower take up and curtailed development. Huge quantitative easing policies have lowered interest rates around the globe, consequently leading to low property yields. Under that scenario, London offices look favourably priced against its European peers. According to BNP Paribas, prime West End yields, despite standing at a near all-time low, are now higher than those of Paris, Frankfurt and Milan.

All investment and take up data and statistics from Savills, unless stated; all performance statistics from MSCI; all graphs by the author.

Stewart Cowe, February 2021