The Global Economy

While the lingering effects of the Covid-19 pandemic are still impacting global economies, it is the indirect effects of the Russian invasion of Ukraine – high energy prices, high levels of inflation and consequently high levels of interest rates – which are currently of more importance.

Pent up demand, continuing (although lessening) supply chain disruptions and high commodity prices have all created the environment for acute price inflation which have recently hit multi-decade highs around the globe, and which in turn have led central bankers to aggressively tighten monetary policies in an effort to bring inflation back towards target levels.

Following many years of ultra low levels of interest rates, this sudden switch of tack has caught out some parts of the financial system, most noticeably in the failures of several regional banks in the US and in the loss of confidence in the global player Credit Suisse. These, hopefully isolated cases aside, the financial system is now better prepared and better capitalised to withstand such systemic shocks such as rapidly increasing interest rates, but bank stocks remain vulnerable to further shocks.

Despite all these headwinds, activity in many countries turned out better than expected in the second half of last year, typically brought about by stronger than anticipated domestic conditions. Labour markets have stayed strong and unemployment rates remain low. Nevertheless, confidence in many countries is currently lower than that prior to the start of the Ukrainian conflict.

The future direction of global economies remains shrouded in doubt. Uncertainty remains elevated and the balance of risks, mainly through renewed concerns over the banking system, has moved even more to the downside.

Our global growth forecasts see a further 10 basis points (bps) trimmed from both this year’s and next year’s expectations compared to our views three months ago, but starkly, our new forecast of 2.8% for this year marks a significant downgrade of 1 percentage point (pp) from our expectations for 2023 made immediately before the outbreak of war.

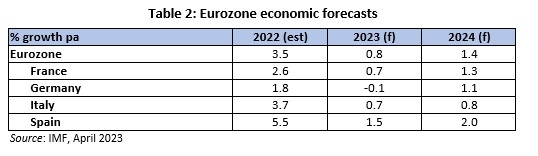

The EU Economy

GDP growth in Q1 of 0.1% following the previous quarter’s flat-lining certainly ensured that the euro zone escaped falling into recession. Recent surveys point to a more upbeat second quarter but even so, the odds are strengthening of a slowdown and possible recession in the second half of this year.

Industrial activity has been the main contributing factor to the zone’s resilience recently, benefiting from a large backlog of orders and helped by reducing supply problems. This catch-up boost to output will end soon, more so if demand continues to drop.

Of particular concern in the Q1 data was news that retail sales fell by 0.4% compared to the previous quarter leading to the likelihood that total household consumption will also have contracted in the quarter. That decline followed a 0.9% fall the previous quarter. Compounding this reduction was news that the sales decline accelerated in March when sales were 1.2% lower than in February.

Industrial production struggled in March after rising the two previous months. French industrial output fell by over 1% in March while a near 3% fall in manufacturing output in Germany is a signal that its industrial output will also be down. A huge fall of almost 11% month-on-month in industrial orders in the zone’s biggest economy in March was the country’s biggest monthly fall since the first Covid lockdown three years ago and this has reduced orders to their lowest since August 2020.

Further interest rate increases are expected from the European Central Bank, following May’s 25 bp increase, which would pile even more pressure on hard-pressed households and businesses.

Compared to our previous report, we have increased our GDP expectation for the euro zone this year by 10 bps but lowered the 2024 expectation by 20 bps. As with our forecasts for other economies, risks to these forecasts lie firmly on the downside.

The UK Economy

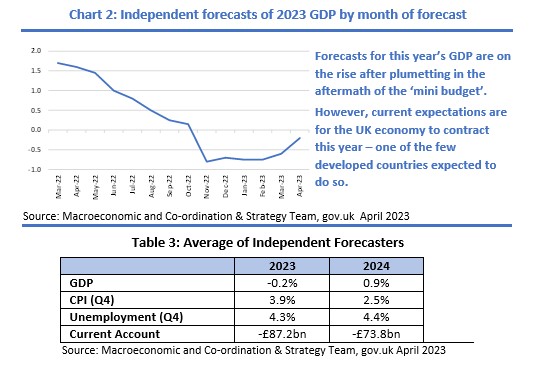

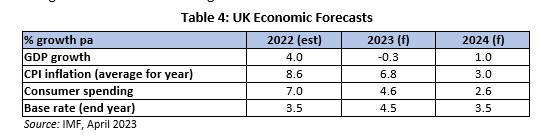

The UK, once again, grabbed unwanted headlines in April when, according to the IMF, Britain would deliver the worst economic activity over 2023 in the G7 group of countries. Commentators conveniently forgot the fact that the UK enjoyed one of the strongest levels of growth in the G7 last year and looking at the cumulative growth over last year and this, the UK comes out third of these seven countries and two full percentage points of growth greater than the worst performing economy by this measure, Germany. The IMF’s new UK forecast contraction of 0.3% for 2023 was, though, a little better than the organisation’s previous forecast of -0.6%.

But much has changed since the publication of the IMF’s report. Recent data suggests that a recession (defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth) may be avoided this year; albeit current expectations for a year’s growth of around 0.2% would still indicate only an anaemic performance. By contrast, Britain’s stubbornly high rates of inflation, where annual rates have now been above 10% for nine consecutive months, suggest that at least one further increase in base rates can be expected, perhaps as soon as the May meeting of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. That outcome is certainly worse than expectations three months ago.

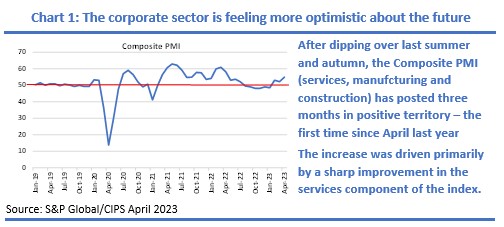

The more optimistic view on the economy can be seen from the recent uptick in the Purchasing Managers’ Index, which has indicated an expansion of activity for the last three months. The April figure was the highest since April 2022. Further good news has emerged from a rise in consumer spending, defying expectations of a contraction owing to the cost-of-living crisis.

The inflation picture remains depressing. Sustained annual rates above 10% were not what was anticipated. Retailers and economists believe that the increase in food prices – the key reason for the recent high rates – will soon reverse. Dismayed shoppers will only believe it when they see their weekly shopping bills start falling. Commentators now no longer suggest that inflation will revert to target this year, but have indicated that it will not be until the end of 2024 before the 2% level is hit.

Meanwhile, news that business failures surged again over Q1 was a timely reminder that the current economic backdrop remains hostile for many businesses. Company failures in England and Wales hit 5,747 over the first three months of the year, 18% higher than during Q1 2022 and one of the highest quarterly figures in 60 years of compilation (source: Azets Accountants). Further increases in interest rates will only compound the problem.

The jury is still out on whether the UK can avoid a recession, or indeed if it can even post growth for 2023. There remains a wide spread of GDP forecasts for this year (ranging from a low of -1.5% to a high of 0.5%), but in the main, these have been improving since the immediate aftermath of the then-Prime Minister’s botched growth plan in September. It should be noted that Chart 2 and Table 3 below were compiled between the 4th and 14th April, since when survey data has appeared more optimistic.

In line with previous reports, we adopt the views of the IMF, which forecasts that the UK economy will contract this year by 0.3%. The small difference between the IMF’s expectation and the above consensus figure is well within rounding errors.

Market Commentary: stability returns to the market, but for how long?

Given the renewed concerns over the banking system which surfaced in March and which the industry has since been unable to quash, it was perhaps surprising that returns from commercial property that month turned positive (source: MSCI Monthly Index, March). Maybe, in the same way that the bond market hiatus of last September was only felt in the commercial property market the following month, a similar story will emerge for returns in April.

Nevertheless, after eight months of declines, average property valuations returned to growth in March – albeit a miserly 0.2%. But drilling down, growth remains patchy. Retail warehouses and industrials – the elements of the property markets which enjoyed strong growth in the bull markets prior to mid-2022 (and coincidentally, the areas of the market that had the biggest falls over these eight months) were the only main segments to show any growth. (The ‘other’ sector, comprising a disparate mix of assets such as leisure, health and hotels also recorded growth, of 0.3%).

The 1.3% increase in average retail warehouse valuations helped all retail assets to increase by 0.8% over March while the average industrial asset increase that month was 0.7%. Offices remain very much in the doldrums. A 1% fall in March takes the Q1 decline to 3.1% and a fall of 17.7% from its peak.

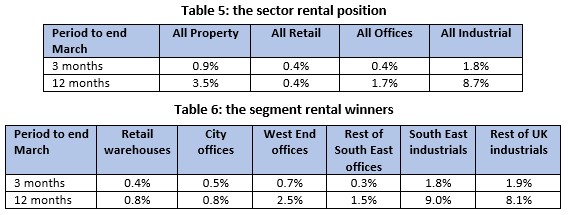

Looking at the performance of the Quarterly[1] Index, the Q1 rental growth picture was positive, as can be seen in Tables 5 and 6. Conversely, only retail warehouses managed to post positive capital growth. Every segment of the market is witnessing growing rents over both the last three months and 12 months. Standing out once again is the industrial sector which recorded average rental growth of 1.8% in the three months to end March and a remarkable 8.7% over the last 12 months.

[1] The Quarterly Index is published every three months & comprises 8,222 UK commercial properties, valued at £142bn. The Monthly Index is much smaller, a total valuation of £29.7bn across 1,561 properties and is published monthly. The Quarterly Index includes properties which are valued at least four times a year while the Monthly Index includes only properties which are valued every month. While much smaller and less representative of the wider real estate market, the Monthly Index can provide a more dynamic view of turning points in the market.

Only one segment has seen its average property values increase over 2023 so far – retail warehouses with growth of just 0.8% while over the last 12 months, no segment has managed to contain the fall in values to less than 10%. Over that period, the best performing segment was shopping centres with a fall in average values of 10.9%

These tables confirm that the property story has all been about the rapid yield unwinding, particularly over Q4 2022, but still evident during the most recent quarter. Over the last three months, yield expansion was still evident across every sector and segment bar retail warehouses where yields hardened by 8 bps to 6.69%.

Surely not another GFC-type crash?

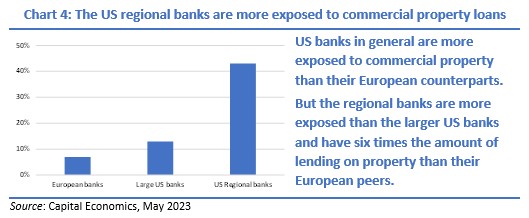

Some commentators are comparing the troubles facing the US regional banks to the liquidity and solvency crisis of the Global Financial Crash. The collapse of several specialist and regional US banks and the forced takeover of Credit Suisse ought not imply that the entire banking system is broken. As stated before, banks are better capitalised now and their loan to value figures are much more benign this time.

That said, one must be aware of the potential risk these US regional banks place on the wider economy. This group of banks are far more exposed to commercial property lending than their European (and UK) counterparts: in Europe, commercial real estate accounts for roughly 7% of banks’ loan books compared to 13% for the larger US banks and 43% for these regional US banks. Hence the worry that failures of these smaller institutions could prove problematical for commercial real estate.

What is alarming, however, in this digital age, is the ease and speed that individual depositors’ money can be moved away from any institution that appears vulnerable. Whereas most commentators had believed the shake out would have been cured by the quick and pro-active central bank action, lingering doubts about the viability of some regional banks remain. As each week passes, further doubts about specific institutions emerge, creating a similar measure of distrust that was prevalent in 2007 and 2008. These regional banks are not subject to the rigorous stress testing that applies to the main US and European banks. Another reason why rapid changes of sentiment to these regional banks occur.

Coupled with a likely rise in UK interest rates, this renewed concern about the solvency of these banks has certainly affected the immediate outlook for UK commercial property.

From property’s point of view, yields which have seen sharp outward movements, most noticeably during the last quarter of 2022, seem to have stabilised with the MSCI Monthly Index for March showing very small uptick in average capital values – the first time since June last year. Further yield slippage, though, cannot be ruled out, particularly given the distinct possibility of further increases in UK base rates. That said, any further increase in property yields should be relatively minor and not at the levels seen in Q4 2022. As mentioned above, property valuations are also being supported by relatively strong rental growth, particularly in many industrial markets and in some office locations.

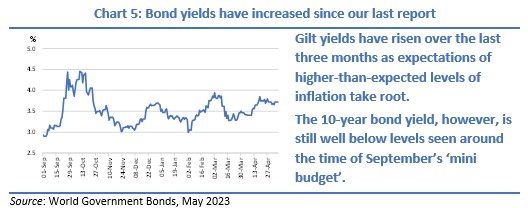

Interest rates in many countries have been ratcheted up since our last report. The increases from the Federal Reserve and from the European Central Bank and the probable increase from the Bank of England later this month had not been factored in three months ago. In the UK’s case, increases will certainly impact the commercial property market, increasing the cost of debt and making some developments and some debt-fuelled investment purchases unviable. As stated earlier, property yields, having appeared to stabilise, may nudge up a little. It is noticeable that the 10-year government bond yield is roughly 50 bps higher than it was three months ago, reflecting the Bank of England’s fight against the higher-than-expected inflation.

That change in the UK’s macro picture is likely to impact the outlook for commercial property. Directly, through higher property yields and indirectly, through changes in the risk premium required by investors. Stock markets have been extremely volatile, some investors are adopting a ‘risk off’ approach, seeking ultra-safe assets. As noted in the following paragraph, property investors continue to sit on the sidelines, so what will tempt them back in? Will property yields need to move even higher for them to do so? Having said that, property fundamentals remain supportive. The recent shake out has undone much of its over-valuation, rents are still edging up while development, by and large, is modest.

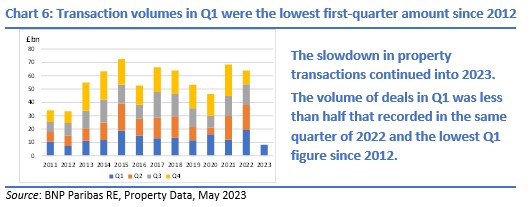

Total investment over the first three months of the year was just £8.3bn, 55% below the equivalent period last year and the lowest Q1 figure for 11 years. Compared to the first three months of last year, industrial deals were down 80% and office transactions were less than half last year’s. Only in the retail sector did the volume of deals approach those of Q1 2022 – but retail transactions of £1.9bn included Sainsbury’s £431m portfolio deal, more of which can be read in the retail section later in this section.

Given the speed and extent to which market rates of interest have been rising – twelve months ago, base rate was just 1.0% – vendors and buyers have not been quick to adjust to the current levels. Sales that completed during Q1 were predominantly put on the market last year while open marketing of new properties for sale remains limited. This all suggests that Q2 transaction figures will also be modest. One hopes that after the traditional summer lull, more certainty about the levels of interest rates will attract increasing numbers of participants to the market over the last six months of the year.

As the cost of borrowing has increased, the amount lent by banks has slowed, particularly with lending for development projects. Net lending for developments has been negative for each of the last nine months (and for 26 out of the last 29 months) (source: Capital Economics) suggesting that the provision of Grade A properties over the medium term will be limited. This net reduction in bank lending is not simply down to the banks’ reluctance to lend – the rising costs of materials and higher financing costs are making many potential developments unviable. That said, the reduced number of developments in the future highlights the fact that, at current levels of take up and demand, the provision of Grade A space in the coming months is unlikely to keep pace with demand. This augers well for prime rental growth in the coming months and years.

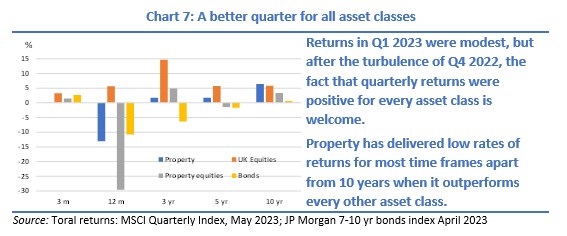

Total returns stabilised over Q1 despite acute volatility in March following the initial burst of concern for the solvency of some US banks. At least total returns were positive (commercial property delivering a minimal 0.1% total return over the quarter) but property’s poor performance over the previous quarter ensures only modest rates of return over the longer term.

The industrial sector

Industrial assets bounced back over Q1 following its fall from grace in Q4 2022. Growth in valuation terms, though, was accompanied by lower take up and investment deals. Take up dropped 15% to 8.6m sq ft from the previous quarter and Q1 was the third successive quarterly decline (source: Colliers Marketbeat, Q1 2023).

This fall in take up was accompanied by a change in tenant composition. There were fewer large tenancies signed with an increase in smaller units, as logistics companies and retailers sought to acquire space to safeguard against supply chain disruption and manufacturers continued to increase their near-shoring and re-shoring operations. Medical sector occupiers have recently been ramping up space requirements, helped by the UK pharmaceuticals and life sciences sectors.

Availability has risen over the quarter, up 7% in the three months to 60m sq ft (source: Colliers Marketbeat), yet supply remains tight. Development, too, is increasing. Currently, Colliers reckon that over 200m sq ft is being built speculatively, an increase of 40m sq ft in the quarter.

Q1 investment transactions were the lowest first quarter figure for ten years but sentiment seems to be improving as investors note that average equivalent yields have risen by over 125 bps (to 6.15%) over the course of the last nine months (source: MSCI Quarterly Index).

The retail sector

A better than feared Christmas season has brought some optimism back to the retail market. While still suffering from the cost-of-living crisis, recent sales data has been encouraging with some retailers, particularly fashion operators, announcing expansion plans and/or moves to reopen outlets in locations where they had previously operated.

The squeeze on consumer spending shows little prospect of an early conclusion, but as inflation subsides, retail spending should recover. Spending will benefit from the low levels of unemployment and when wage growth, at some point, once again outstripping inflation.

Investment in retail assets was not as badly hit in Q1 as the other sectors, down just 19% to £1.3bn. But as indicated earlier in this report, a sizeable portion of that investment was attributed to a portfolio deal by the grocery chain Sainsbury to buy the freehold of some of their supermarkets. Sainsbury spent £431m buying the 51% of the Highbury and Dragon REIT they did not own, which contains 26 supermarkets and which are all leased back to them. Sainsbury clearly took on board the comment in our last report which stated that supermarkets were an attractive proposition following the 13% fall in valuation over Q4.

The office sector

Occupier focus across Britain continues to be on prime space. Part of the rationale is to be able to attract, retain and engage staff while ESG considerations are also playing a role with companies becoming increasingly aware of their own carbon footprint.

Fears that the days of the office were numbered, following the work-from-home mantra of the pandemic, seem to be overdone. According to the Office for National Statistics, almost one-in-three office workers now opt for hybrid working, more than double the number who now work solely from home.

Demand for the best office space is noticeable across every major centre in the UK, although some occupiers are marrying this requirement with shrinking the amount of space needed. A combination of slightly lower levels of take up and continuing development have pushed vacancy rates up in just about every main office centre, rising to about 8% in central London and between 5% and 7% in the ‘big-6’ office locations, about 1 pp higher than the five-year average.

Summing Up

We were optimistic three months ago that the sharp downward lurch on property values was at an end. Since then, muted levels of take up and investment were not unexpected given the still uncertain path of interest rates and economic growth around the world.

What has changed over the last three months, however, is the appearance of another ‘black swan’: that of the health of the US banking system. Whereas it was initially expected that any damage to the financial system would be soon contained, as we write, further concerns continue to break, casting a shadow over the outlook for the US economy.

While this issue seems mostly to involve the US financial system, the UK is impacted, if only by sentiment. Additionally, high inflation is pushing up interest rates further than had been expected. Property yields will correspondingly be under further (slight) upward pressure, potentially delaying the embryonic recovery.

Property fundamentals remain supportive. The recent (Q4) shake out has removed much of the over-valuation that had been evident for some time while take up, though weaker than previously, has been quite resilient.

Going forward, much will depend on how successful the Bank of England’s fight against inflation is and how much higher interest rates need to go. The US regional bank issue clearly muddies the water, but directly, will have little impact on commercial property in the UK. Indirectly, it will, and sentiment will play an important role in how investors perceive risks in real estate assets.

The outlook for UK commercial property on a medium-term view looks favourable. What is uncertain in its trajectory over the immediate short term.

Central London offices

The fact that letting statistics and investment transactions are running well below recent levels should not come as a surprise. Uncertainty over the future path of interest rates, made worse by the hiatus last autumn over the ‘mini budget together with more recent overseas banking troubles have cast a shadow over what traditionally is the most volatile of property segments.

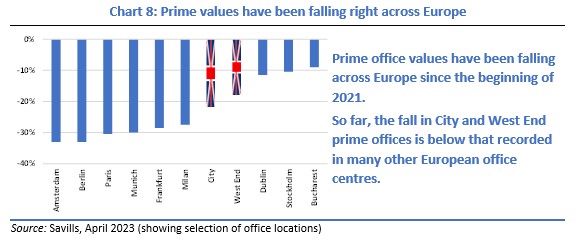

London is not the only key office market to be affected by such worries. European office markets, including Paris, Frankfurt and Milan are all seeing slowing levels of take up and investment transactions. Savills research shows that prime city office values have fallen across Europe since the beginning of 2022 ranging from a fall of 33% in Amsterdam and Berlin to an as-yet less badly hit Bucharest which has seen a modest 9% fall. For comparison, Savills state that City of London prime values have fallen 22% while prime West End values have fallen 18% (in both cases more than the MSCI Quarterly Index’s City office fall of 15.9% and West End’s fall of 10.4% over the same time frame).

MSCI’s monthly data shows that average central London office values have been declining for the best part of a year – for 11 months in the case of City offices and nine months for West End offices – and short term, further valuation falls can be expected. Outward yield movements are the principal contributing factor to these declines, as rents – both at the MSCI ‘average’ office level and at the prime end of the market – are remaining not just remarkably resilient but are still increasing.

One key message that recent take up figures are showing is that of many tenants seeking ‘best in class’ accommodation. Over half of the space let in central London over Q1 was of BREEAM[1] standard ‘Excellent’ or above. And it is not just the large global firms that are favouring such properties; over a quarter of such space let in the City over the first three months of the year was to tenants acquiring space between 15,000 and 25,000 sq ft. It is this focus that is likely to keep prime rents firm over the near term, almost irrespective of rising supply. The same cannot be said for poorer quality space. There will always be tenants seeking ‘cheap’ space, but with the minimum energy efficiency standards (MEES) now in force, some older, inefficient buildings will become unlettable and would have to undergo modernisation.

Take up both in the City and in the West End in Q1 was well down on the 10-year averages (by 21% and 20% respectively) but perhaps surprisingly, the West End take up of 792,000 sq ft was 7% higher than that over the same quarter of 2022. Emphasizing the point that tenants are seeking quality accommodation, 92% of City lettings in the quarter were for Grade A space while four out of the five largest West End deals in Q1 were pre-lets.

A feature of recent reports has been the lengthening transaction process, which has impacted negatively on completed deals. This, though, gives some certainty about future levels of lettings. Both in the City and the West End, the amount of stock under offer at the end of March was well ahead of historic quarterly levels. Over 2.5m sq ft was under offer across both sub markets, an increase of 50% from the long-term average. That gives some comfort that levels of take up will improve throughout the year.

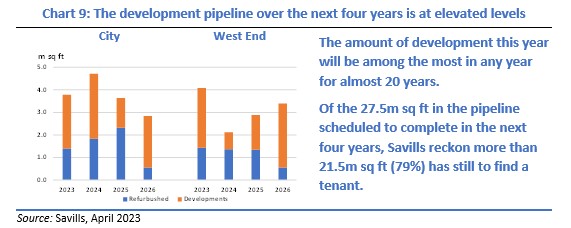

As reported in the previous section, rising interest rates together with increases in the costs of building materials have delayed the start of some developments. Nevertheless, the amount of space anticipated to come to the central London office market in the next four years totals 27.5m sq ft, which, though 1m sq ft lower than that expected three months ago, is well up on historic levels. Of that, 21% has been pre-let, signifying that around 21.5m sq ft is speculative. Coupled with high vacancy levels at present which are equivalent to a similar amount of space, that is a lot of potential space to fill. Take up in the City and West End offices markets combined over the last 10 years has averaged 10.6m sq ft; the potential future supply of roughly 42m sq ft therefore equates to four years of demand – a quite daunting statistic.

[1] The Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Methodology measures the environmental impact of an asset in the built environment.

Valuations continued to slide in the first quarter of the year, but not at the extreme level of the previous quarter. However, a pricing standoff between buyers and sellers remains. Consequently, central London investment deals were sharply down over Q1 compared to the same quarter of 2022 and that of the long-term average. The West End was particularly affected by the slowdown, with only 13 deals totalling £713m occurring in the quarter. Notably, the sellers of all these properties were UK owners.

Like the lettings market, investment deals are taking longer to crystallise. Every property bought in the City during Q1 was under offer at the end of last year. A total of £1.25bn of offices are presently under offer there – almost half is accounted for by two City offices – while there is further evidence of UK investors forsaking the West End as UK owners account for two-thirds of all the openly marketed properties so far this year. Whereas UK investors are selling, Asian investors are buying, particularly GIC (the Singapore Sovereign Wealth Fund). In February, GIC bought 75% of the Tribeca development scheme in NW1, adding to its purchase of Paddington Central last April. Taken together, GIC have accounted for 20% of the total West End transactions by value over the last 12 months.

The performance of City offices and West End offices has been diverging for some time and Q1 2023 was the clearest example of that. The total return of West End offices over Q1 was -1.0%, substantially better than that of the City’s -3.7%. Over the last 12 months, there is a 5½ pp difference between the office markets- the latter delivering a return of -11.2% against the former’s -16.7%. As indicated earlier, rental growth is stronger and the outward yield shift less pronounced in the West End market.

All investment and take up data and statistics from Savills, unless stated; all performance statistics from MSCI; all graphs by the author.

Stewart Cowe, May 2023